What are Re/Marks?

Re/Marks are a form of annotation.

Re/Marks are critical. Critical because these notes critique—re/marks are annotations that contest power, social inequality, and oppressive ideology. And re/marks are critical in that these notes are necessary, highlighting (in)justice and inscribing possibility.

You're no doubt familiar with book marginalia as a common form of annotation. Marginalia are added by kids and adults to their books, often privately, and for many reasons. Marginalia are usually idiosyncratic and are seldom re/marks.

In contrast, re/marks are distinguished by an ability to appear both on pages and in places, for these critical annotations alter surfaces of the built environment and our everyday social settings. With re/marks, annotators can compose and make comprehensible new justice-centered narratives.

Here's my formal definition from Re/Marks on Power:

Re/Marks are annotation traces collectively read and (re)written so as to advance counternarratives and more just social futures.

What might these traces look like?

Not all historical markers and local place markers are annotations, much less re/marks. However, as I write about in the second chapter of Re/Marks on Power, twenty-five triangular place markers along the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway throughout Maryland help compose new civic narratives about Black resistance, liberation, and the struggle for social justice.

This is a re/mark, annotating a legacy and land:

Not all murals are annotations, much less re/marks. However, as I write about in the third chapter of Re/Marks on Power, the addition of Mural de la Hermandad, the Deported Veterans Mural Project, and the Playas de Tijuana Mural Project to the wall demarcating the US-Mexico international boundary at Playas de Tijuana demonstrate how an annotated border line communicates grounds truths of solidarity and dignity.

This is a re/mark, annotating a barrier and boundary:

Not all signs, like plaques or interpretive commentary, added to public monuments are re/marks. However, as I write about in the fourth chapter of Re/Marks on Power, public protestors who alter—even temporarily—our memorial landscape with paint, blood, graffiti, cloth, yarn, or projections help contest problematic historical messages and oppose harmful ideology.

This is a re/mark, annotating a statue and symbolism:

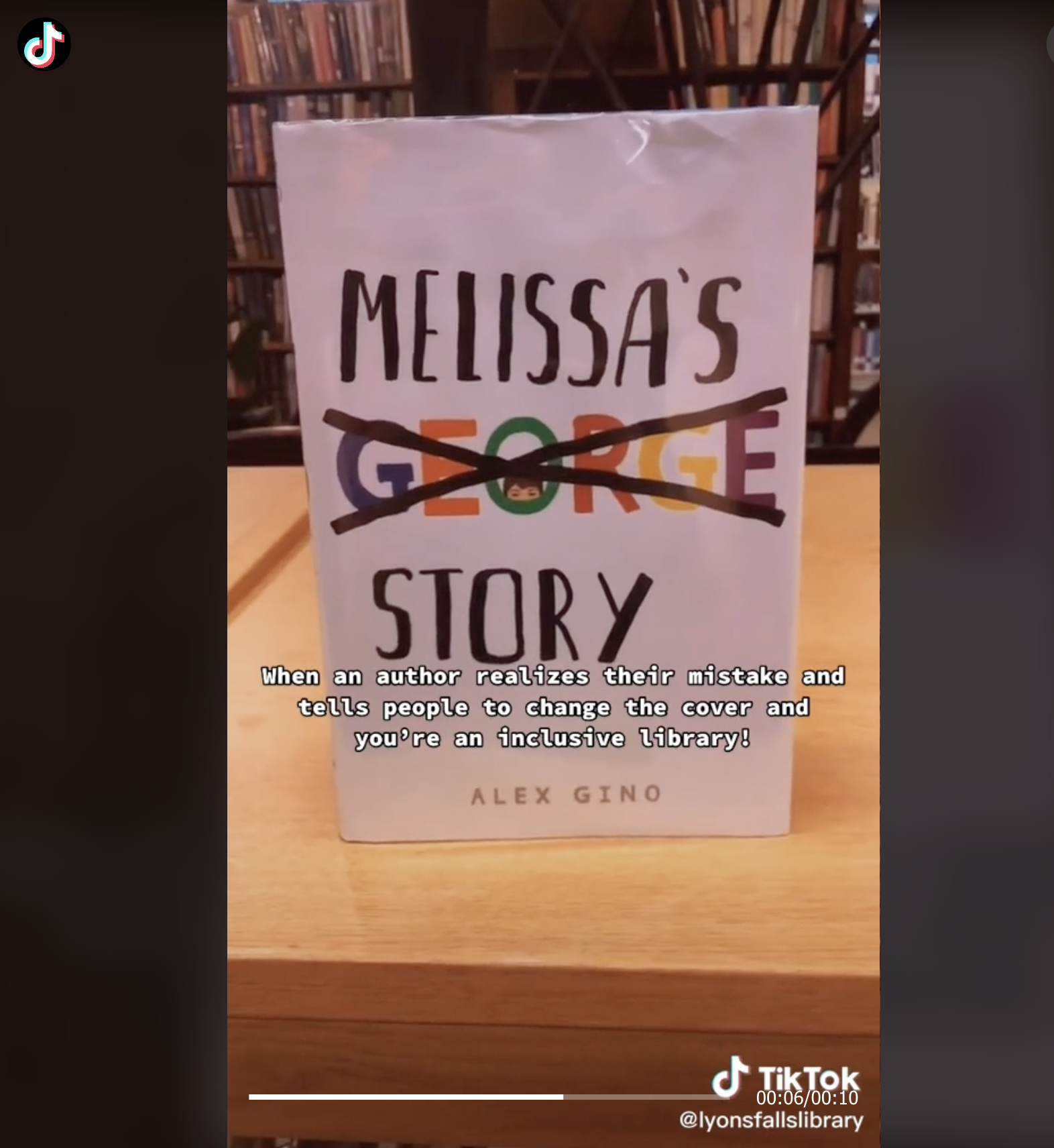

Not every alteration made by a librarian to a book is a re/mark. However, as I write about in the fifith chapter of Re/Marks on Power, public and school librarians utilized annotated books to circulate messages of activism and affirmation about LGBTQIA+ justice through their participation in #SharpieActivism.

This is a re/mark, annotating a cover and counternarrative:

Annotators add notes to texts. Annotators who add re/marks to texts contest power and document struggles for justice.

As I write in the conclusion of Re/Marks on Power:

The social life of re/marks eclipses the conventional forms and reductive purposes of annotation, for these participatory traces are a means by which people write historical memory, resist harmful ideology, and broadcast solidarity and social change. Across four cases, I sought out and analyzed an original category of annotation—as located in archives and libraries, on walls and books, atop maps and monuments, and along byways and all manner of margins—to detail how such notes advance counternarratives and envision justice-directed social futures.

I hope this newsletter brings together, and helps to sustain, a community of annotators interested in the enduring power and possibility of re/marks. If that includes you, please:

- Read Re/Marks on Power: How Annotation Inscribes History, Literacy, and Justice

- Share examples of your re/marks

- Subscribe to Reading Re/Marks

Know an annotator who should be featured in Reading Re/Marks? Send me a note!

Member discussion