Re/Marks on Annotation

Re/Marks on Power: How Annotation Inscribes History, Literacy, and Justice arrives next Tuesday, April 15.

Just days from publication, my excitement is tempered by the fact that words I wrote a few years ago could have been written yesterday:

I write at a moment of entrenched partisan debate in the US about public education and what historical facts and perspectives may be taught in school, how memory and cultural heritage is honored in civic settings, and whose identities and stories are sustained by our institutions.

My book about critical annotation—this academic study about a thing I call re/marks—emerges in conversation with our moment of great trauma and precarity.

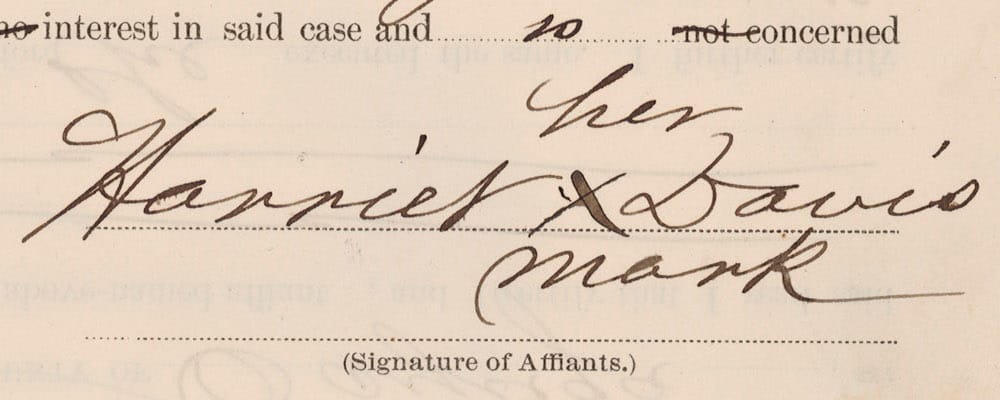

For instance, Re/Marks on Power arrives at a time when public recognition of Harriet Tubman’s life and legacy remains contested. It was reported, just days ago, that the National Park Service removed Tubman's photograph and words from a webpage about the Underground Railroad. Then, earlier this week, the page was revised yet again following public outcry. In the second chapter of my book, I celebrate Tubman's literacies and her mark-making, for she was an annotator. Her mark is as necessary today as it was when it first appeared on paper in 1890.

Re/Marks on Power arrives at a time when the border wall at Playas De Tijuana, erected along the US-Mexico international boundary, is taller than when I visited two years ago. Much of the art and annotation that I documented along this fraught border has been removed, including my contribution to the barrier that appears on my book’s cover. As of last week, there's even more razor wire. Since this margin was first marked in 1848, it has been an unnatural and increasingly fortified boundary; and yet, as I observe, "Ground truths and testimonials will continue to be written along this line."

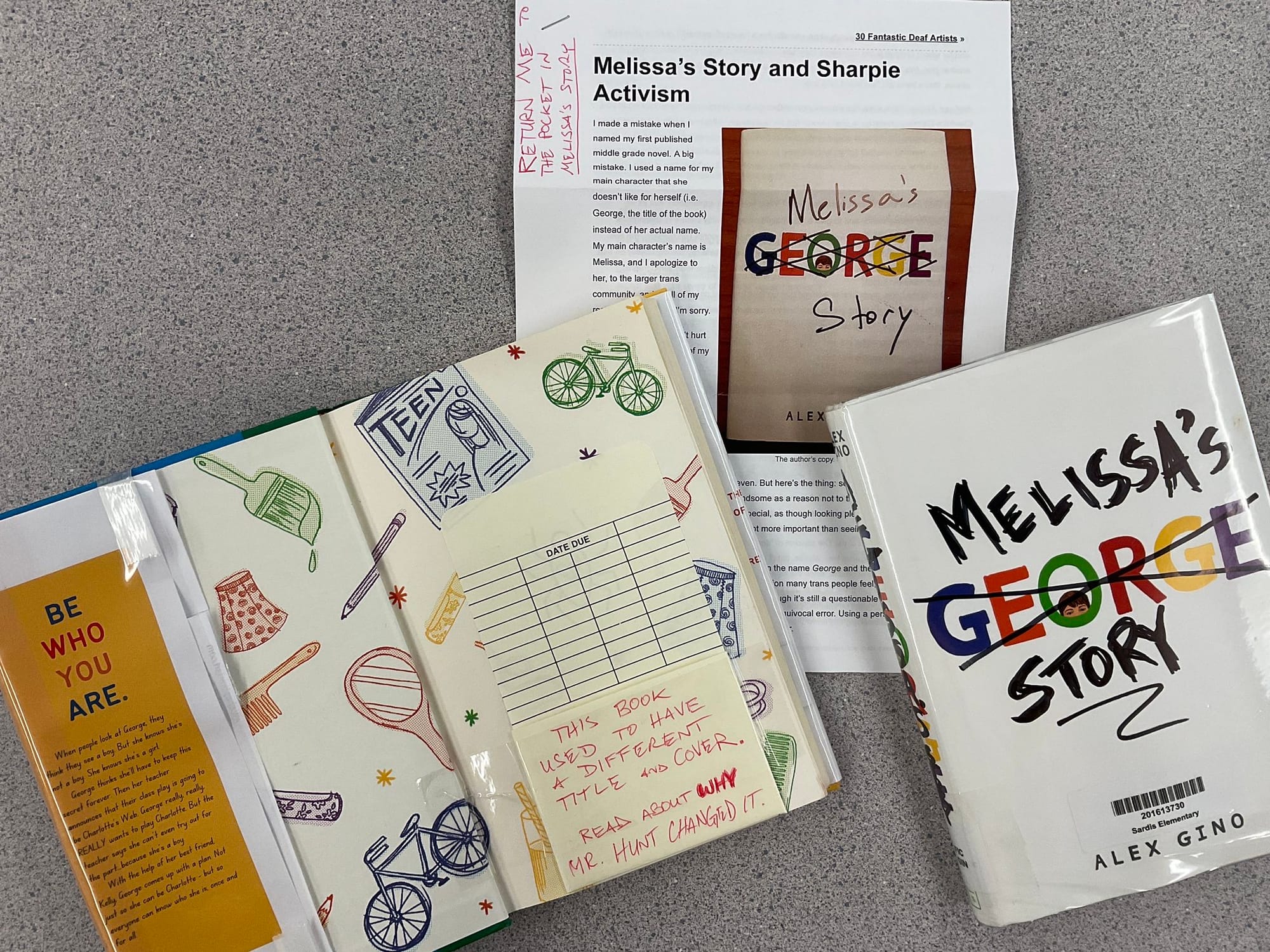

Re/Marks on Power also arrives at a time when book banning continues across the country. Coincidentally, it's National Library Week. A few days, the American Library Association released its annual list of most challenged book, noting that: "The most common justifications for censorship provided by complainants were false claims of illegal obscenity for minors; inclusion of LGBTQIA+ characters or themes; and covering topics of race, racism, equity, and social justice." In the fifth chapter of my book, I uplift the stories of public and school librarians who annotated the middle grade novel Melissa with and for their students as an opportunity to remark on trans pride and justice. Last year, according to data from PEN America's Index of School Book Bans, Melissa was banned in four school districts in Florida, eleven in Iowa, as well as by districts in Texas and Wisconsin.

In light of the broader social and political circumstances within which Re/Marks on Power will appear next week, today's post features an extended excerpt from my book's introduction.

What follows will give you a sense of why I wrote this book, how I sought a particular tone for this text, and how I approached my craft as an annotator and author. I hope that with this bit of writing, minimally edited for the purposes of this post, you can better glimpse what to expect as a reader. As I write:

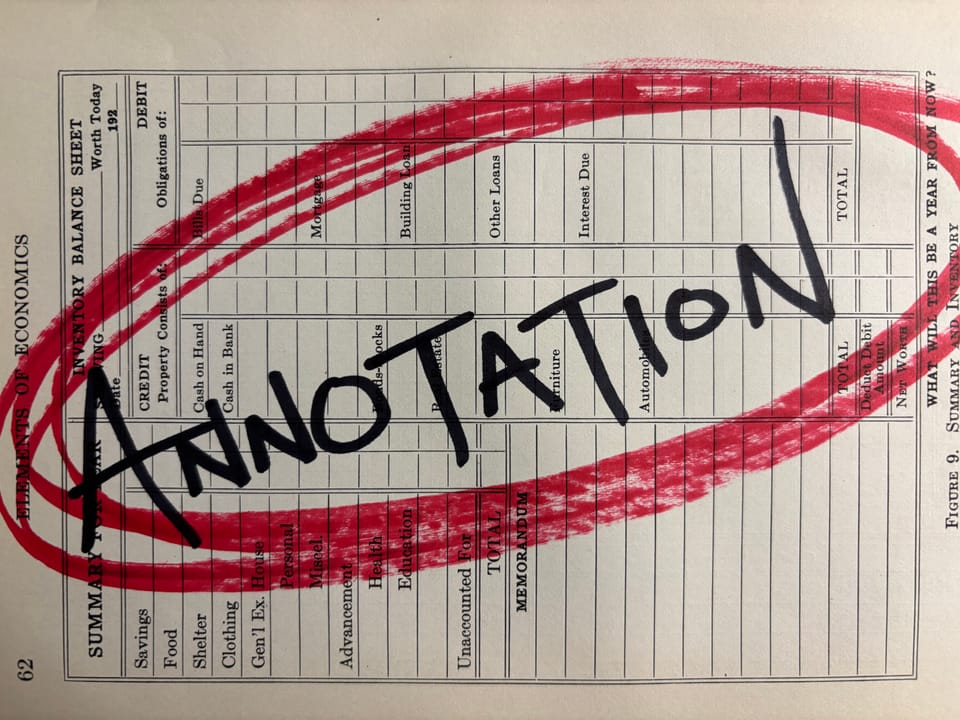

Given shifting conceptions of literacy and learning, and in a moment of deep concern about equitable schooling and society, it is time for a fresh read and rewrite of annotation.

Enjoy these re/marks on annotation.

"As an annotator, three arguments ground my rationale for redefining the possibilities of annotation. First, annotation is more than book marginalia. From textbooks to town squares to TikTok, annotation manifests as a hybrid act producing divergent marks that thrive outside the tightly bound pages of a book. Second, the social life of annotation is as impor tant as individual reader response. Annotation must be studied and promoted as a social endeavor coauthored by groups of mark-makers, with interactive media, spanning on-the-ground and online settings, and in response to shared commitments. Third, annotation is a critical practice; it is an essential act that inscribes struggles for justice and social change. Annotation should be embraced as exemplifying, and helping to extend through embodied and digital spaces, a critical literacy lineage through which annotators—including learners in school—read and write words so as to critique and change their worlds.

My three arguments about annotation—as critical and in dialogue with (in)justice, as hybrid and thriving beyond book marginalia in everyday settings, and as social and privileging civic activity rather than private response—encompass an intent to reintroduce and represent annotation as the creative, communal, and essential expression of readers-as-writers. These arguments also make clear my stance toward literacy and learning and how I understand what it means to learn and participate in literacy practices. In their book Living Literacies, Kate Pahl and Jennifer Rowsell show us how literacies are “historically situated sets of social practices that are highly dependent on what people do with literacy.” Annotators do annotation and, as I document, this literacy practice is associated with many sources and spaces beyond printed books. Consequently, educators who read this book might reconsider referencing a broader repertoire of everyday texts for students to read, annotate, and discuss, including historical records, walls, monuments, social media, and landmarks. Furthermore, because annotation is a social practice that facilitates peer collaboration and negotiated meaning, we should help learners, including classroom teachers, rewrite reader response when authoring annotation about their academic and everyday interests. And because annotation is a critical practice enabling critique and contextualization, we can promote the shared addition of notes to texts as annotators craft counternarratives. The creative possibilities of annotation are apparent and relevant to learners’ lives, as well as their critical literacies and civic activities.

I write about the critical, hybrid, and civic qualities of annotation because literacy and learning practices reflect power. How does access to material resources shape the types of notes people add to texts? Whose knowledge is welcomed and celebrated when texts are annotated? And in what ways does annotation reveal valued cultural practices and social dreams? This book spans contexts, from literacy education to participatory politics, as I chronicle how the annotation of everyday texts is a confluence of authority and resistance, an amalgam of agency and imagination. It has been over two hundred years since the term “marginalia” appeared as a neologism, and well over a millennium since Roman emperors and their handwritten annotatio remarked on rulings and imperial power. Given shifting conceptions of literacy and learning, and in a moment of deep concern about equitable schooling and society, it is time for a fresh read and rewrite of annotation. For centuries, scholars have both written and studied what Jackson categorized as three “basic particles” of historical annotation: glosses that translate and explain terminology; rubrics that mark headings and index sections; and scholia that comment on and contextualize a primary source. To this set I add a contemporary form: re/marks.

I work, through this book, to recast annotation as implicated in peoples’ meaningful and socially vital activities, as woven into multimodal texts and cultural contexts, and as mediated by everyday language and power. To do so, I propose the concept of re/marks, which I define as annotation traces collectively read and (re)written so as to advance counternarratives and more just social futures. This term makes prominent the inherent hybridity and visual assertiveness of annotation as both a textual disruption and social intervention. As for the scope of re/marks, you may read my emphasis on “more just social futures” as an untoward aspiration for something as seemingly unremarkable as annotation. Indeed, our ability to follow annotation traces over texts and time does not indicate an achievement of social justice. Rather, my intent is to show that the actions of annotators are legible, longstanding, and instructive amidst the ongoing project of shaping a pluralistic society that values equality and affirms human dignity. My original concept is a useful heuristic for demonstrating how people’s recursive marks have highlighted, literally and metaphorically, the continued struggle against social inequality and oppressive ideology. And my research will show that those who closely read everyday symbols and spaces, and who then compose additive responses of resistance and imagination, are annotators—for their pursuit of more just social futures has been visualized through traces we can call annotation."

Book Talk and Annotation Jam at Duke

For friends and colleagues around Durham, North Carolina, I'm excited to announce a book talk and annotation jam for Re/Marks on Power on April 21!

I'm honored to have this event hosted by Duke Learning Innovation & Lifetime Education and Duke University Libraries, scheduled for Monday, April 21 from 4:30 to 5:30 in Rubenstein Library 153 (Holsti-Anderson Family Assembly Room).

The event is free and you can register here.

Know an annotator who should be featured in Reading Re/Marks? Send me a note!

Member discussion