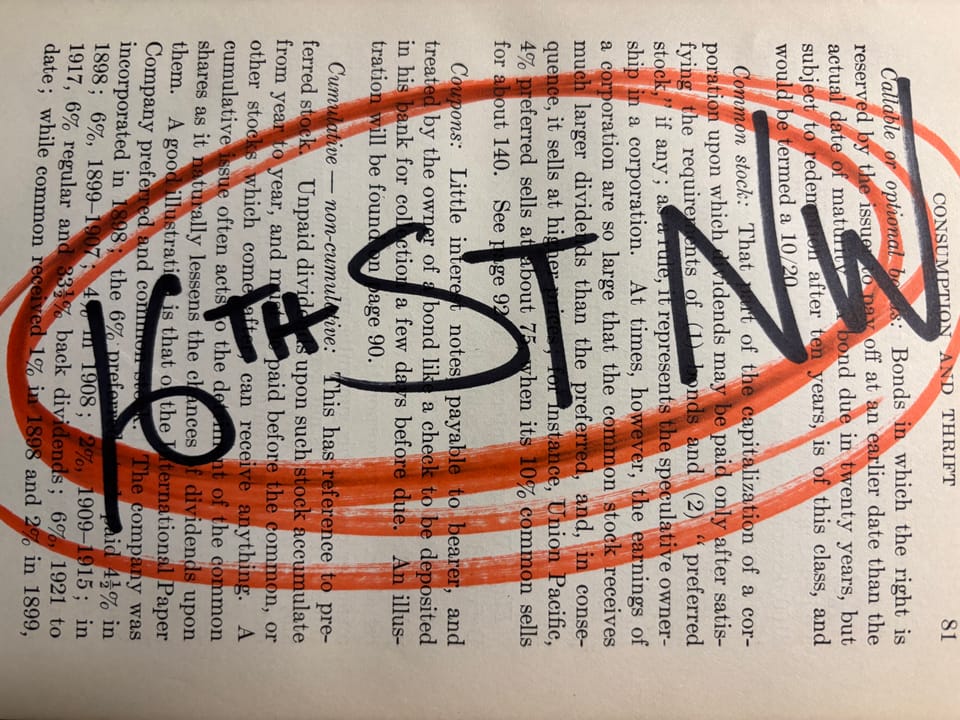

Re/Marks on 16th St NW

An anonymous annotator wrote the two-word annotation on a large yellow letter. That letter, one of sixteen, appeared underfoot along the brick street. I read the annotated re/mark as a land-mark on a landmark. Both, presumably, are no longer legible.

Earlier this month, construction crews began to remove the Black Lives Matter street mural that was painted in large, yellow block letters along 16th St NW in Washington, DC. In the summer of 2020, the two-block long mural transformed a stretch of ordinary pavement in the nation's capital into a pedestrian zone renamed Black Lives Matter Plaza. The district’s three-word mural—so large it was easily read in satellite imagery—was the first of many similar declarations that inscribed America’s cityscapes that summer.

I glimpsed the handwritten re/mark—a small accent, an affirming echo—added to the mural when I last visited Washington, DC, in February of 2023. The marked mural was a civic composition, a dynamic canvas of critical annotation and expression.

I offer nothing original by noting that prominent symbols and slogans are both celebrated and criticized by adherents of divergent ideological commitments. For some, words are hollow if unaccompanied by actions that alter the material conditions of people’s wellbeing and dignified livelihoods. Alternatively, for others, words are hostile if accompanied by actions that recognize the myriad complexities of a nation’s history and systemic injustices. So it was, and so it remains, with Black Lives Matter. Words and symbols are contested precisely because the messages we highlight—whether in our speech or on our streets—convey social meaning and communicate power.

Indeed, if the political craft and control of words and discourses were trivial, then the recent introduction of H.R.1174—to force the removal of the Black Lives Matter mural in Washington, DC—wouldn’t have been introduced. The bill's title, alone, functioned as a partisan threat that has subsequently prompted large-scale civic erasure. It reads:

“To amend title 23, United States Code, to withhold certain apportionment funds from the District of Columbia unless the Mayor of the District of Columbia removes the phrase Black Lives Matter from the street symbolically designated as Black Lives Matter Plaza, redesignates such street as Liberty Plaza, and removes such phrase from each website, document, and other material under the jurisdiction of the District of Columbia.”

This bill, its title and text, the exercised threat, and the explicit redaction remind me of something I observe in the introduction of Re/Marks on Power: How Annotation Inscribes History, Literacy, and Justice, available on April 15. In contextualizing my arguments about the social life of annotation, I write:

“You have likely glimpsed fraught relationships among readers and texts, notes and norms that are contested and in revision whether online, at school board meetings, or as displayed by place markers and symbols of the built environment.”

In following this news, I also recall what Charles Blow aptly described, in the spring of 2022, as “The Great Erasure,” or an attempt to erase from public art and public discourse both a movement and a moment that was “declaration and confrontation, brazen and assertive. It was forcefully in your face.” Blow offered this analysis, noting:

“There is no example of this erasure more striking than the continual destruction, removal or slow vanishing of much of the street art produced in the wake of [George] Floyd’s killing.”

The slow vanishing of place-based words and symbols was aggressively accelerated by H.R. 1174 and, with it, modest yet meaningful re/marks—like “Black LIVES!!!”—that emended the 16th St NW mural. I wrote much of Re/Marks on Power throughout the 2022-23 academic year and, since then, some annotations that I encountered while conducting on-the-ground research have disappeared, whether incidentally or intentionally. And that now includes the re/mark added to 16th St NW, just steps from the White House.

Yet why mention such a small re/mark, this simple “Black LIVES!!!” annotation? After all, it likely weathered from exposure to the elements and may have entirely disappeared well before this month’s events. Moreover, we might easily write off the note as literally pedestrian, for an anonymous passerby wrote but two words and three exclamation points atop three other words, and then just moved along with their day.

One reason is because we cannot take for granted the ability to publicly express affirming counternarratives to dominant ideology. I emphasize the importance of such civic literacy throughout Re/Marks on Power, and the argument will also be a recurring theme in this newsletter. The annotator who wrote this re/mark reminds us that simple acts of public affirmation are a necessary form of resistance, and that everyday text should be visibly reinterpreted so as to interrupt status quo convictions. As I ask in the conclusion of Re/Marks on Power:

“Re/marks evidence annotators responding to problematic surroundings and dominant discourses. While reading your worlds, where might this form of annotation aid comprehension of controversial symbols and spaces?”

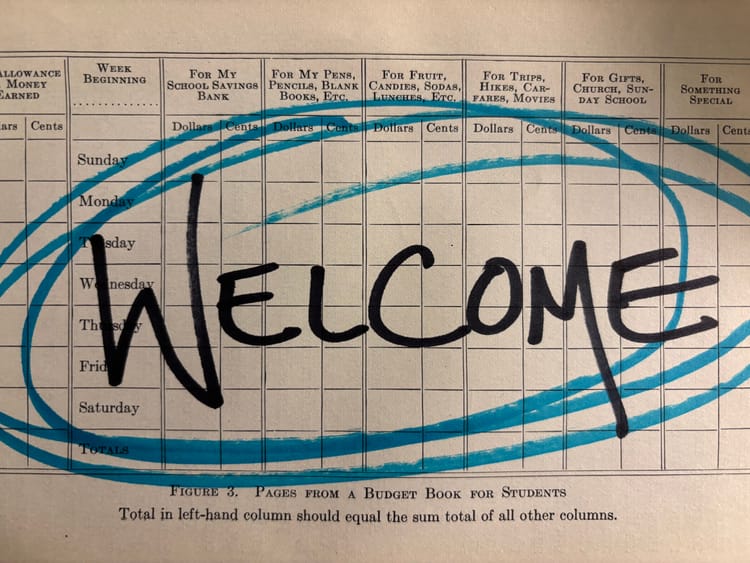

And a second reason is because we cannot only expect to observe critical annotation in conventional texts, such as books. As readers of words in our world, we must strategically shift our gaze away from the page and toward, for instance, acts of land-marking that visibly alter the messages and meanings of everyday settings. In Re/Marks on Power, I quote historian John Stilgoe from his 1998 book Outside Lies Magic: Regaining History and Awareness in Everyday Places. Stilgoe offers a useful analogy for how we can understand some acts of annotation as place-based land-marking:

“The built environment is a sort of palimpsest, a document in which one layer of writing has been scraped off, and another one applied. An acute, mindful explorer who holds up the palimpsest to the light sees something of the earlier message, and a careful, confident explorer of the built environment soon sees all sorts of traces of past generations.”

The annotator who wrote “Black LIVES!!!” interpreted Black Lives Matter Plaza as a discursive landmark, the first layer of a public palimpsest. They also understood how their land-marking would leave a trace for future “explorers” of the built environment, like me, to further comprehend shifting social and semantic geographies.

Echoing the disappearance of words and terms from government documents, the events about and along 16th St NW earlier this month are further evidence that those with ascribed political authority are making use of their power to forcefully rewrite our built environment and cultural landscape.

Recent Podcast Interviews

I've had the great pleasure of discussing Re/Marks of Power in two recent podcast interviews.

First, I joined literacy educator and researcher Trevor Aleo on his podcast Conceptually Speaking.

Here's how Trevor describes our conversation from the show notes:

[Remi] has also completely revolutionized my thinking about annotation. As someone who was relatively ambivalent about annotations, Remi's perspective transformed me into a fan, believer, and enthusiastic practitioner. Our conversation challenges conventional wisdom about annotation, as Remi argues that we're all annotators...

For educators struggling to make annotation meaningful beyond compliance, this episode offers both theoretical insights and practical inspiration to transform this everyday practice into something that can, as Remi says, "live, speak, and inspire."

Trevor has also turned the episode's transcript into a Google Doc that listeners and readers can mark up with comments if you'd like to participate in some social annotation. Thank you, Trevor!

And second, I joined researcher and educator Helen Beetham on her podcast imperfect offerings.

Much of our conversation concerns my day-to-day role supporting educational research and faculty development, specifically in relationship to generative AI. However, Helen and I do discuss Re/Marks on Power and annotation, leading to this lovely exchange halfway through the episode:

Remi: ... [my book is] looking at four cases, all of which have historical roots around the ways that everyday readers, folks well beyond formal educational contexts, are reading a whole variety of texts and adding their notes, whether they're eminent or anonymous, to texts to try and contest dominant ideology or reshape narratives towards more just social futures. That's the core argument of my new work.

Helen: It's so important, isn't it, to remember that writing text is absolutely occupied by power and always has been. I mean, I would never be one to say that writing has not been used to oppress people, to oppress peoples, to hide powerful knowledge away in cabals and priesthoods. And what you illuminate there, though, is just in the same way that text is our cultural memory and our cultural monument in many, many cultures of the world, we have also evolved practices of speaking back to power through text...

During our conversation, I also share with Helen two books that creatively feature annotation and critical re/marks: Christina Sharpe's Ordinary Notes, and Reginald Dwayne Betts and Titus Kaphar's Redaction (which I wrote about here). Thank you, Helen!

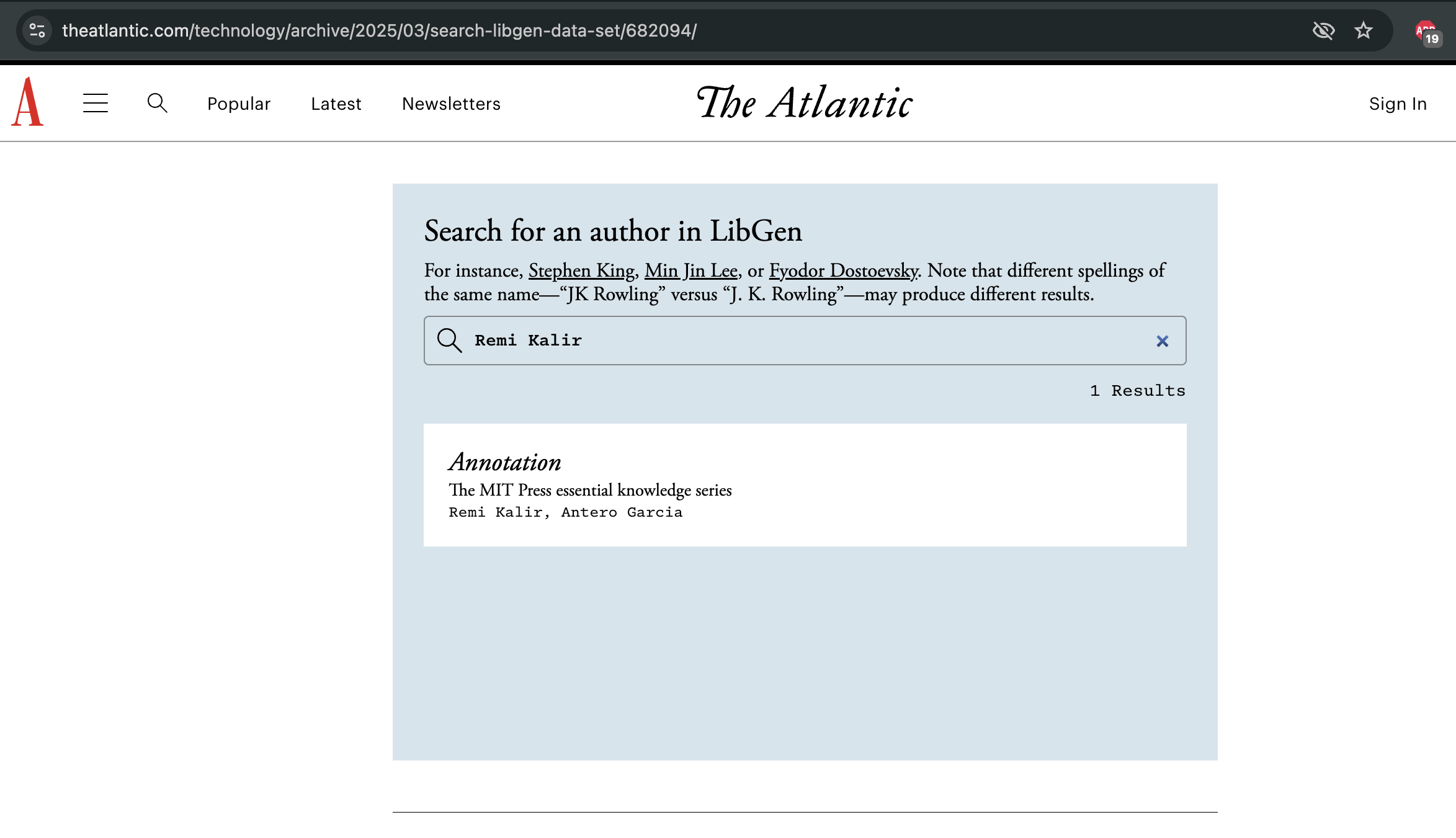

Annotation in LibGen

Last week, The Atlantic released a search tool for Library Genesis (or "LibGen"), the data set of pirated material used to develop generative AI systems by Meta.

Annotation, my first book co-authored with Antero Garcia and published by MIT Press, was illicitly scraped as training data and included as a part of LibGen. Same for some of my peer-reviewed research, such as articles that appeared in leading academic publications like Journal of Literacy Research and TechTrends.

If you're an author or academic and haven't yet done so, search LibGen here.

Last word this week goes to Captain Renault: "I'm shocked, shocked to find that gambling is going on in here!"

Pre-order Re/Marks on Power from your preferred retailer.

Know an annotator who should be featured in Reading Re/Marks? Send me a note!

Member discussion